Basic HTML Version

The Islamic Bulletin

Volume X X No. 26

Page 4

Written by Sebatian R. Prange

a

Photographed by Aasil Ahmadd

W

HILE HE WAS

A

LAW

STUDENT

, T

HOMAS

JEFFERSON

BOUGHT

A

NEWLY

PUBLISH

E

NGLISH RENDITION OF THE

Q

UR

’

AN

. W

HAT CAN

THAT

PURCHASE

TELL US ABOUT HIM

? A

BOUT HIS

POLITICS

,

AS AN

AMBASSADOR

AND

AS

THIRD

PRESIDENT

OF

THE

U

NITED

S

TATES

.

O

R

ABOUT

THE

LEGACY OF

RELIGIOUS

FREEDOM

AND

PLURALISM

THAT HE

LEFT TO

THIS COUNTRY

?

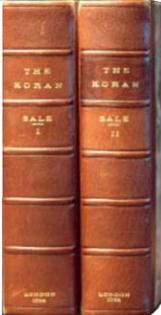

Facing the United States Capitol in Washington,

D.C. stands the Jefferson Building, the main building of the

Library of Congress, the world’s largest

library. . . The stately building…is

named after Thomas Jefferson, one of the

“founding fathers” of the United States,

principal author of the 1776

Declaration

of Independence

and, from 1801 to 1809,

the third president of the young republic.

But the name also recognizes Jefferson’s

role as a founder of the Library

itself…Among the nearly 6500 books

Jefferson sold to the Library was a two-

volume English translation of the Qur’an,

the book Muslims recite, study and

revere as the revealed word of God. The

presence of this Qur’an, first in

Jefferson’s private library and later in the

Library of Congress, prompts the

questions why Jefferson purchased this

book, what use he made of it, and why he included it in his

young nation’s repository of knowledge.

These questions are all the more pertinent in light

of assertions by some present-day commentators that

Jefferson purchased his Qur’an in the 1780’s in response to

conflict between the us and the “Barbary states” of North

Africa—today Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia and Libya. That was

a conflict Jefferson followed closely— indeed, in 1786, he

helped negotiate a treaty with Morocco, the United States’

first treaty with a foreign power. Then, it was relations with

Algeria that were the most nettlesome, as its ruler

demanded the payment of tribute in return for ending

semiofficial piracy of American merchant shipping.

Jefferson staunchly opposed tribute payment. In this

context, such popular accounts claim, Jefferson was studying

the Qur’an to better understand these adversaries, in

keeping with the adage “know thy enemy.” However, when

we look more closely at the place of this copy of the Qur’an

in Jefferson’s library—and in his thinking— and when we

examine the context of this particular translation, we see a

different story.

From his youth, Thomas Jefferson read and collected

a great number of books… The collection he eventually sold

to the Library of Congress comprised 6487 volumes…

Jefferson not only cataloged his books but also marked

them. The initials “T.J.” were Thomas Jefferson’s device for

marking his books: On this page, the “T.” is the printer’s

mark to help the binder keep each 16-page “gathering” in

sequence, and the “J.” was added personally by Jefferson.It

is his singular way of marking his books that makes it

possible to establish that, among the millions of volumes in

today’s Library of Congress, this one specific Qur’an did

indeed belong to him.

Jefferson’s system of cataloging his library sheds

light on the place the Qur’an held in his thinking. Jefferson’s

44-category classification scheme was much informed by the

work of Francis Bacon (1561-1626), whose professional

trajectory from lawyer to statesman to philosopher roughly

prefigures Jefferson’s own career. According to Bacon, the

human mind comprises three faculties: memory, reason and

imagination. This trinity is reflected in Jefferson’s library,

which he organized into history, philosophy and fine arts.

Each of these contained subcategories: philosophy, for

instance, was divided into moral and mathematical;

continuing along the former branch leads to the subdivision

of ethics and jurisprudence, which itself was further

segmented into the categories of religious, municipal and

“oeconomical.”

Jefferson’s system for organizing his library has often

been described as a “blueprint of his own mind.” Jefferson kept

his Qur’an in the section on religion, located between a book on

the myths and gods of antiquity and a copy of the Old

Testament. It is illuminating to note that Jefferson did not class

religious works with books on history or ethics—as might perhaps

be expected—but that he regarded their proper place to be

within jurisprudence.

Jefferson organized his own library, and he shelved religious

books, including his English version of the Qur’an, with other

works under “Jurisprudence,” which fell under “Moral

Philosophy. “The story of Jefferson’s purchase of the Qur’

helps to explain this classification. Sifting through the records of

the

Virginia Gazette

, through which Jefferson ordered many of

his books, the scholar Frank Dewey discovered that Jefferson

bought this copy of the Qur’an around 1765, when he was still a

student of law at the College of William & Mary in Virginia. This

quickly refutes the notion that Jefferson’s interest in Islam came

in response to the Barbary threat to shipping. Instead, it situates

his interest in the Qur’an in the context of his legal studies—a

conclusion that is consistent with his shelving of it in the section

on jurisprudence.

Jefferson’s legal interest in the

Qur’an

was not without

precedent. There is of course the entire Islamic juridical tradition

of religious law

(Shari’ah)

based on Qur’anic exegesis, but

Jefferson had an example at hand that was closer to his own

tradition: The standard work on comparative law during his time

was

Of the Law of Nature and Nations

, written by the German

scholar Samuel von Pufendorf and first published in 1672. As

Dewey shows, Jefferson studied Pufendorf’s treatise intensively

and, in his own legal writings, cited it more frequently than any

other text. Pufendorf’s book contains numerous references to

Islam and to the

Qur’an

. Although many of these were

disparaging—typical for European works of the period—on other

occasions Pufendorf cited Qur’anic legal precedents approvingly,

including the

Qur’an’s

emphasis on promoting moral behavior, its

proscription of games of chance and its admonition to make

peace between warring countries. As Kevin Hayes, another

eminent Jefferson scholar, writes: “Wanting to broaden his legal

studies as much as possible, Jefferson found the

Qur’an

well

worth his attention.”

“We the General Assembly of Virginia do enact that no

man shall be compelled to frequent or support any religious

worship, place, or ministry whatsoever, nor shall be enforced,

restrained, molested, or burthened in his body or goods, nor

shall otherwise suffer, on account of his religious opinions or

belief; but that all men shall be free to profess, and by argument

to maintain, their opinions in matters of religion, and that the

same shall in no wise diminish, enlarge, or affect their

civil capacities”(From the Virginia Statute for Religious

Freedom, ratified 1786;drafted by Thomas Jefferson in 1777).

In his reading of the Qur’an as a law book, Jefferson

was aided by a relatively new English translation that was not

only technically superior to earlier attempts, but also produced